(via http://twitter.com/IFVP)

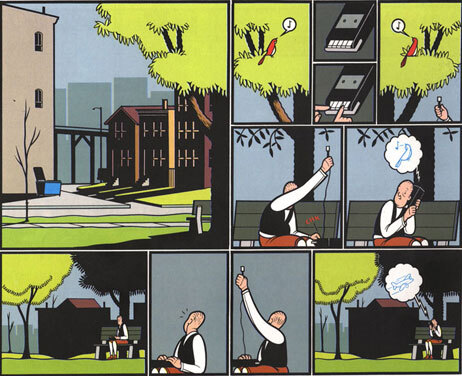

Jimmy Corrigan, The Smartest Kid On Earthis an example of a comic where the art is doing its job.(Random House)

Jimmy Corrigan, The Smartest Kid On Earthis an example of a comic where the art is doing its job.(Random House)

Glen Weldon posts on NPR Arts correspondent Lynn Neary's piece on All Things Considered about the new graphic novel adaptation of Ray Bradbury's classic Fahrenheit 451. He breaks down what's right and what stinks about the last generation of graphic novels, and how the masters of the form make it work.

Attention to Tension

That's the feeling you get when comics creators allow both text and image to share the load. They can work in concert -- the art amplifying some element of the narration, say, or isolating one character or object to give it greater symbolic weight. Or they can work in opposition -- as when the words tell us one thing, but the art shows us something else.

In books like Maus and Persepolis (forgive me for dusting off the go-to NPR-demo examples), a cartoony style contrasts sharply with the violence and chaos of events depicted.

In a masterpiece like Jimmy Corrigan, The Smartest Kid on Earth, Chris Ware shuts up for long stretches of time, letting his art do all kinds of things on its own. His clean, unnervingly precise linework, for example, tell us something about Jimmy -- something deep and intuitive and heartbreaking that words can't quite get at.

And in an all-ages, cute-as-all-get-out, utterly wordless book like Owly, the art does all the work. Cutely.