Artists Embedded in War

Alphachimp

Alphachimp  Monday, January 10, 2005 at 10:35PM

Monday, January 10, 2005 at 10:35PM

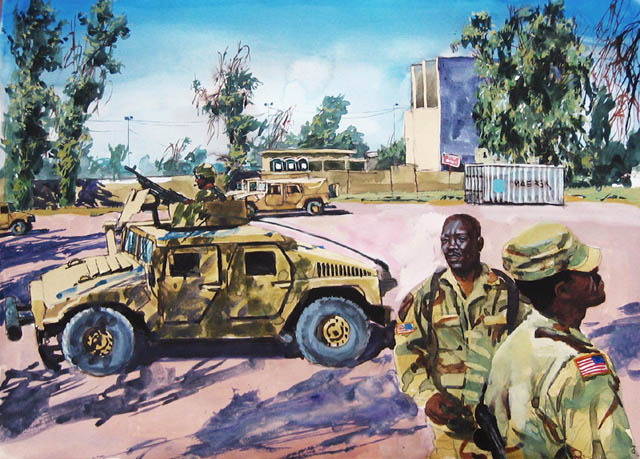

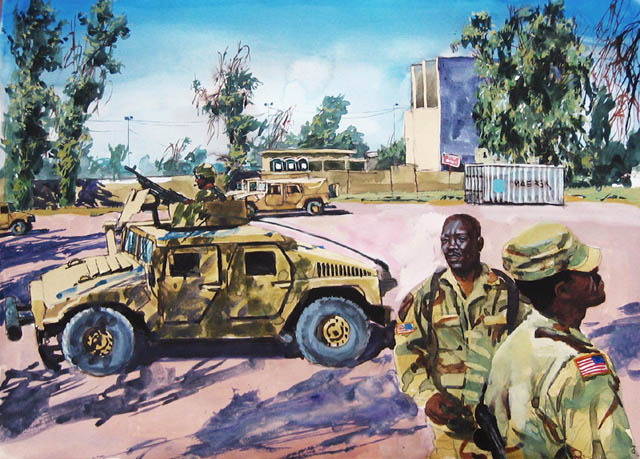

Forward Operating Base (FOB) Cuervo in Baghdad. Steve Mumford, 2004.

Much has been made of the embedded journalists in Iraq, but what of other types embedded artists?

This week's show of NPR's This American Life with host Ira Glass, was titled "In Country: Stories from inside Iraq". It included interviews with Arkansas National Guardsmen stationed a few miles from Baghdad and clips from a new documentary TV series about them, Off to War, on the Discovery channel.

This unit shipped to Iraq with trucks manufactured between 1956 and 1964. Only four of 44 vehicles had proper armor when they arrived. The documentary follows several soldiers and their families back home.

During the First Gulf War, Executive Producer of the documentary, Jon Alpert, entered Baghdad at the height of the bombing. He was the only TV reporter able to get out of the country with uncensored footage. He provided the first documentation of extensive civilian deaths caused by the bombing. His reports were awarded the Italian Peace Prize by the president of Italy. One year after the war, Alpert returned to Baghdad to conduct an exclusive interview with Saddam Hussein.

Brothers, Brent and Craig Renaud, were born and raised in Little Rock, Ark and have been working with Alpert since 1995 on projects in Afghanistan, Cambodia, Bolivia, China, Pakistan and Iraq.

Listen to NPR's Scott Simon interview with the Renaud Brothers, Weekend Edition - Saturday, November 6, 2004.

The same show also profiled Steve Mumford, an embedded artist creating sketches and paintings of the scenes he's witnessed in Iraq: patrols, arms cache demolitions, raids, roadblocks, and life in Forward Operating Bases or FOBs.

[ More News from Iraq via New York Times International ]

Art and war have been emeshed through the centuries. The 19th century Spanish artist Goya produced hundreds of images, including a vast series of prints, titles "Disasters in War", depicting the ravages of Napoleon's army in Spain.

Francisco de Goya. Desastre de la Guerra, 39; Grande Bazana! Con Muertos! c.1810-1811. Etching and aquatint.

However, it wasn't really until the 20th century that a generation of artists unleashed an unromanticized vision of war after serving in the armies of Europe during World War I.

The Night by Max Beckmann. 1918-19. Oil on canvas. 52 3/8 in x 601/4 in.

Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Dusseldorf

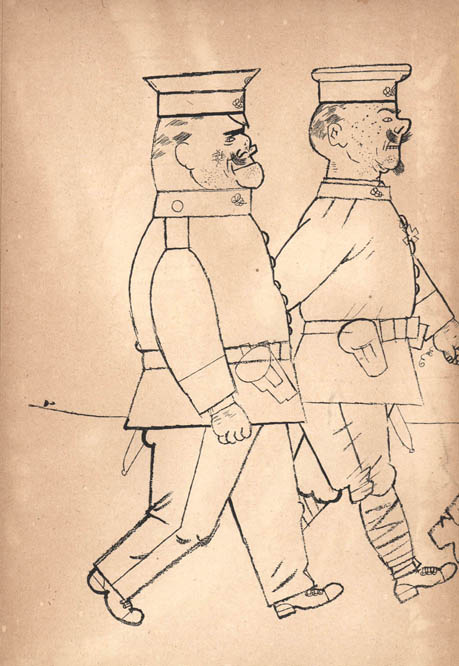

Wieland Herzfelde. Tragigrotesken der Nacht: Träume. Illustrated by George Grosz. Berlin: Malik Verlag, 1920.

Die Bruecke and other German Expressionists, such as Beckmann, George Grosz and Otto Dix, used a fast, aggressive visual language inspired by folk art to convey the emotionally torn fabric of 1920's Europe.

During World War II, young American artists like Ed Reep, were swept up in the conflict as active duty soldiers, but saw the war through the keen eye of the artist.

Soon after graduating from The Art Center School, and five months before the attack on Pearl Harbor, Reep enlisted in the Army as a Private. After getting an assignment as an Overseas Artist, Reep skeched and painted throughout North Africa and Italy. He often found himself in the thick of battle and was repeatedly strafed, bombed, and shot at while painting the war. He was awarded the Bronze Star, promoted twice on the battlefield and left the army as a Captain.

During World War II more than 100 U.S. servicemen and civilians served as 'combat artists'. They depicted the war as they experienced it with their paintbrushes and pens. Their stories have never been told, and for fifty years their artwork, consisting of more than 12,000 pieces has been largely forgotten until the PBS documentary, They Drew Fire, aired in May 2000.

I fought the war more furiously perhaps with my paintbrush than with my weapons. And I always put myself in a position where I could witness or be a part of the fighting. That was my job, I felt. And I was young, kind of crazy, I suppose. ~Ed Reep

Modern day artist Joe Sacco carries that tradition into the evolving genre of comics, graphic novels, and a new form of visual journalism. Sacco takes his first-hand experiences in listening to survivors in Bosnia, the West Bank and Palestinian refugee camps.

Modern day artist Joe Sacco carries that tradition into the evolving genre of comics, graphic novels, and a new form of visual journalism. Sacco takes his first-hand experiences in listening to survivors in Bosnia, the West Bank and Palestinian refugee camps.

His artwork guides us through tense, lucid narratives, packed with detail, in Safe Area Gorazde and his two part masterpiece, Palestine.

The ultimate embedded artist is Art Spiegelman, most famous for his Pulizter Prize winning graphic novel Maus Parts I & II.

His work is inspired by woodcuts and comics from the 1920s and 1930s, and Maus uses the metaphor of cat and mouse in the retelling of his father's experiences as a Polish Jew in wartime Warsaw and Auschwitz, and later as an aging immigrant in New York coping with the loss of his wife.

"Maus is a book that cannot be put down, truly, even to sleep. When two of the mice speak of love, you are moved, when they suffer, you weep. Slowly through this little tale comprised of suffering, humor and life's daily trials, you are captivated by the language of an old Eastern European family, and drawn into the gentle and mesmerizing rhythm, and when you finish Maus, you are unhappy to have left that magical world."

~Umberto Eco

Spiegelman's most recent work, the tabloid sized book reflecting the very real–and very surreal–streets of Manhattan on and after 9/11.

In struggling to find a new visual language to frame the events and convey both the comedy and tragedy of the situation, Spiegelman turned back a hundred years to the masters of the broadsheet comics. In an essay, Spiegelmann explains that the artists of the comic strips our great-grandparents may have read as kids, like the Katzenjammer Kids and Little Nemo, were also dealing with the chaos of their age: urban growth, mass immigration, political corruption, ethnic tension, civil unrest in Europe and the US.

Spiegelman and his family bore witness to the attacks in their lower Manhattan neighborhood: his teenage daughter had started school directly below the towers days earlier, and they had lived in the area for years. But the horrors they survived that morning were only the beginning for Spiegelman, as his anguish was quickly displaced by fury at the U.S. government, which shamelessly co-opted the events for its own preconceived agenda."

~from publishers Random House

Reader Comments